More joined up management of the Welsh moors creating a continuous landscape to restore habitats is the challenge of recovering bird species, says Huw Lavin, who started as an apprentice on the Powys Moorland Partnership project 3 years ago.

With a keen interest in game-keepering from school days, Huw spent weekends and all holiday’s out with a local keeper to learn all the skills needed to protect grouse and all other ground nesting birds.

“It’s the only job I’ve ever wanted,” he says, and after two years at Newton Rigg college he landed a full-time job as a keeper on a grouse moor in Wales which is a rare find.

The main problem in Wales is that grouse has disappeared from most of the heather moorlands over the past 30 years as grouse shooting declined, but Huw believes that if we really want to see them recover along with other ground nesting birds there is still time, just, but many more people are needed on the ground.

He believes that in just three years, despite the weather not being conducive to increasing the grouse population, the number overall has flourished once the management to restore the habitats and keep predators under control was implemented.

“We need more people doing the same thing so that we connect up larger areas of land and create a proper continuous landscape scale programme to recover some key upland bird species,” he says.

But Huw believes the job of a gamekeeper is so much bigger than ever and probably needs re-naming as the role does so much more to boost biodiversity.

“We are very much in the spotlight of the media so we must get our story over in a positive way,” he says, and that means taking in everyone’s point of view. It’s not the fault of the public on how they have formed their views with all the pressure that is out there but, we have a responsibility to make sure we message effectively and not aggressively and that has to start with the children.

Huw has hosted several groups of children from Hay and Clyro primary school to explain his work.

“What is great is that they get it and understand that to protect the ground nesting birds we have to protect them from the masses of predators that the Welsh countryside is full of,” says Huw, who explains that to manage the homes of the grouse, a mosaic of heather needs to be created so there is short heather for the food source and longer heather for shelter and nesting.

We have to keep engaging with the public and find different ways of helping people understand the complexities of moorland management especially as Welsh Government is encouraging more people to get outside and connect with nature.

“It’s a special place to work and moorlands are magical so it’s right that more people should experience it, but respecting each other is going to be the biggest challenge.”

Huw has now moved to a top well established grouse moor in the Angus Glens of Scotland as a grouse keeper where he will be one of 11 keepers.

Catherine Hughes

Sustainable Management Scheme facilitator

History of Red Grouse Shooting

A brief history of red grouse shooting 1900-1960s

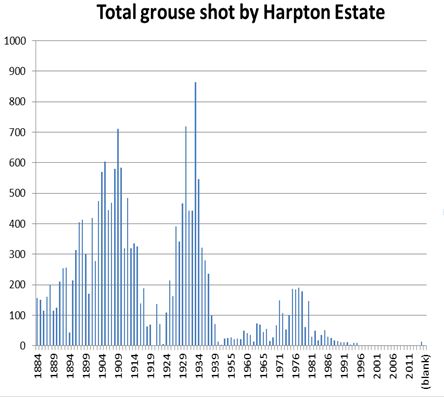

As indicated by the graphs below, from 1900 to the end of the Second World War Powys enjoyed large numbers of grouse. The Beacon hills for example had so many grouse that the owners created a shooting lodge and train station to help people from London to enjoy its sport. It has a section of heather known to many as the Millionaire’s Mile in honour of the grouse drive over this area.

1960s – 1990s

After the War, a great deal of Welsh heather was lost due to conifer planting and the emergence of the Common Agricultural Policy which paid farmers according to stock numbers. Raptor numbers started to increase at the end of this period and grouse eaters like buzzards and hen harriers became protected species in the early 1980s.

By 1990 Ireland Moor and Gladestry were the best areas for grouse, but the number of birds shot and the number of moors with keepers had declined sharply. There were just ten keepered moors in Wales in 1990, with only 640 birds shot that summer.

2010-present

By 2010 there was not a single moor in Wales with a full-time grouse keeper.

The catalyst for change came in 2015 when the Welsh Governments Nature Fund sprinkled seed funding across nine moors, leading to keepers being employed to bring their management expertise to these neglected areas.

Thanks to the combination of Government support and private investment there are currently five full-time grouse keepers in Powys.

Aims for the future

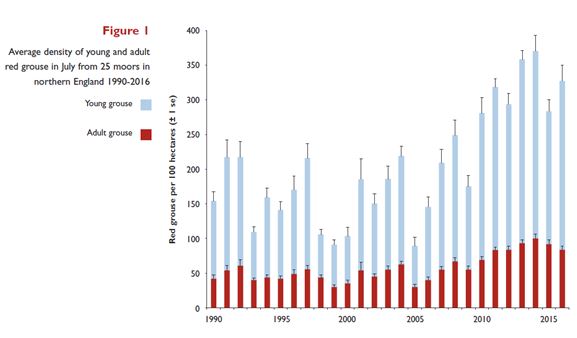

As this Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust graph shows, red-grouse numbers in northern England have recovered well since 1990. In Wales this has not yet happened. Although the aim is not to achieve the densities seen in northern England, we are committed to creating a sustainable surplus of numbers so that we can support shooting of this economically important bird. This will require sensitive land and predator management with the emphasis being on creating sustainability for all – including flora, fauna, human, and community.

The spring count

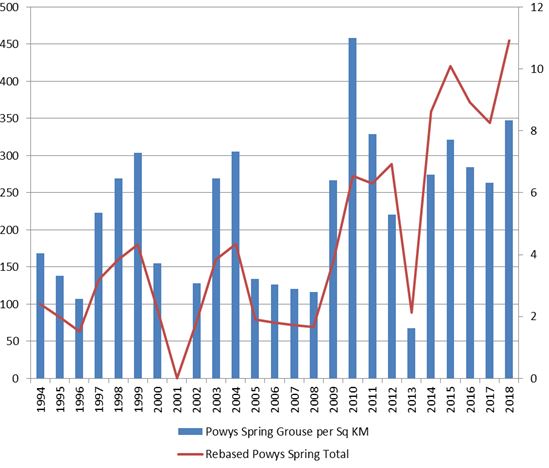

Thanks to many recent years of hard work from the moorland keepers, the recent counting shows that the pairs of grouse this spring are more numerous than they have been since the 1970s.

The area counted is the moors above Painscastle (Ireland Moor) along with Gladestry, Gwaunceste and Beacon hills.

With that said, the percentage of the grouse that died during the winter due to predation and natural causes was over 40% across all Radnorshire moors – the yardstick to aim for is 30%.

This chart shows the grouse per square km (per 100 hectares) and an index of the increase in spring grouse since 1994.

Return of the Welsh grouse

David Thomas is working on an exciting project to restore wildlife to the hills of Powys

Moorland Management

Location: Beacon Hill, Powys

Acreage: 5,000

Percentage in conservation: 100

Funding grants: Sustainable Management Scheme, supported by the Rural Development Programme

Conservation measures: Predator control, brashing, wiping, cool burning, pond digging, and bird surveys.

David Thomas

David Thomas is a gamekeeper on Beacon Hill moor, 5,000 acres of the Crown Estate near Pilleth in Powys, the site of Owain Glyndwr’s famous defeat of the English at the battle of Bryn Glas. The land is grazed by sheep farmers who hold commons’ rights and the shooting rights are rented by a small local syndicate captained by Peter Hood, a retired hill farmer. David’s post is funded by the Welsh Government (WG) as part of the Powys Moorland Partnership which includes three separate moors aiming to restore grouse and other endangered moorland birds.

The project started after the 2013 State of Nature report revealed continued declines of wildlife in Wales. Frustrated that despite a considerable investment in conservation work there was very little success to show, the WG announced a new pilot program called the Nature Fund to deliver environmental, economic and social outcomes through collaborative action within two years. Out of that came the Sustainable Management Scheme (SMS) now funded by the Rural Development Programme. GWCT’s

Teresa Dent and Ian Coghill helped to put together a partnership of land managers and applied successfully to the SMS for funding for the Powys Moorland Partnership and the North Wales Moorland Partnership.

David is in the first year of the current three-year funding programme but has been working full time on the hill for three years. After the initial Nature Fund grant finished in 2015, rather than let the work go to waste, he decided to work for nothing and spent his own money on equipment while waiting for the SMS money to come through.

In the nineteenth century Beacon Hill was a prodigious grouse moor. You can see the remains of a grand Victorian shooting lodge on the hillside and there was even

a railway station to bring guests right up to the moor by train. These days the grouse are clinging on at about 30 brace in the autumn counts and the waders and other moorland species have been similarly reduced. The reasons are complex. Since the 1960s as the great estates disappeared, many of the Welsh uplands were ploughed or planted with woods and the remaining heather moors became isolated.

“Sheep grazing plays a crucial role in keeping down scrub and trees and the farmers on the hill are keen to make the project a success.”

In the 1970s headage payments were introduced under the CAP, which meant farmers received subsides according to the number of sheep on their land. As a result, heather, bracken and grass were over grazed, leaving little, food, nesting habitat or shelter for waders and other birds. Since headage was replaced by area payments after the Foot and Mouth crisis the transformation has been dramatic, with heather and bracken returning to the hillside. David feels the grazing level is about right, except during winter months when ideally the number of sheep would be reduced. Sheep grazing plays a crucial role in keeping down scrub and trees and the farmers on the hill are supportive and keen to make the project a success. It helps that David and Peter were both sheep farmers and they believe most are conservationists at heart. Peter said: They have a soft spot for the hills and the wildlife and they are also tickled pink by the crow control David has achieved.

Overgrazing may have been an issue in the past, but for David the current principal challenge is predation. As with elsewhere in the UK, generalist predator numbers have been increasing steadily. The prime threat to grouse and waders is the fox. The problem lies in the fact that there is no other keepering for grouse or pheasant shoots within 15 miles, so any vacuum created on the hill is quickly filled. Covering 5,000 acres on his own is a big challenge for David. Use of GWCT approved humane snares is essential and they are deployed in a highly targeted manner. A night vision rifle scope is also invaluable as foxes can be alarmed by the infrared lamp. If he

is after a particular fox. David regularly stays up several nights in succession until the small hours of the morning and is still not guaranteed success.

I’m currently putting in an 80-hour week. If it’s dry and there’s a full moon I lamp four or five hours every night. This winter I’ve accounted for 85 foxes up here and each year I get more because I’m getting better at it, but it’s still the tip of the iceberg. Another keeper described the hill as the perfect place for predators as it’s an island moor.

In addition to foxes, avian predators, in particular carrion crows, take the eggs and chicks of ground-nesting birds in the breeding season. David controls them by means of Larsen and ladder traps and has caught about 2,700 in the past three years. His trapping line, which includes tunnel traps for stoats, weasels and rats takes five hours to check every morning. Crow numbers may also have been boosted by less lambing on the hill. Peter explained: Farmers used to control crows because they would kill the newborn lambs. These days you see many who will walk under a crow’s nest without noticing.

Grouse can be found on areas of the moor where they hadn’t been when David started and on one part of the moor numbers have trebled according to this year’s spring counts, but they are starting from a low base and the challenge is great. Other birds species are making a more rapid recovery including mistle thrushes and skylarks and cuckoos can now be heard in profusion in spring. These like to lay their eggs in meadow pipit’s nests, which have also increased. Hare numbers have boomed and so too have kestrels and merlins. This year, more extensive bird counts will be carried out for the first time so progress can be mapped more accurately. Another endangered species to have benefitted, which is close to David’s heart is the curlew. He said: We have managed to increase curlew broods on the hill, which I am delighted by. When you hear the bird’s call on the moor at the end of February, it’s the first sign of spring and I stop to admire the sound spilling from the sky, equalled only by the skylark.

“Everyone involved knows we need to share this special place with everybody.”

Impressive results on Beacon Hill and other moors in the partnership have fed into the Shropshire & Welsh Marches Recovery Project, a grassroots curlew conservation campaign run by Amanda Perkins. Notes based on GWCT science are now being used as guides by the local community groups involved in the project.

Another large part of David’s work is restoring a balance of habitat by creating a patchwork of heather, bracken, white grass and moss as well as digging ponds to provide water for grouse and to attract insects. In the past, the heather was either overgrazed or allowed to grow too tall and large areas have been overtaken by bracken, which is controlled by wiping the plants with herbicide rather than spraying to avoid damage to the grass and moss beneath. Younger heather can be brashed (cut) and the older, leggier areas show far better restoration through burning. David has initiated a ten-year rotation of small areas of cool burn to avoid damaging the moss and peat underneath. One of the biggest challenges is the tiny window. He explained, Our permitted burning period is two weeks shorter than in England and Scotland. You need three clear sunny days and no snow to burn and because there is so much rainfall it is difficult to keep within the timeframe.

Wildlife Highlights

Red listed

- Cuckoo (left)

- Winchat

- Curlew (inset)

- Mistle thrush

- Ring ousel

- Skylark

- Hen harrier

Amber listed

- Grouse

- Kestrel

- Meadow Pipet

- Merlin Hobby

- Brown hare

Members of the shoot volunteer their time to lend a hand with brashing and burning. They release a few redleg partridges every year for two informal shoot days. Peter, whose family has held the shooting rights since 1950 explained: Our way of shooting is very unusual it’s similar to a family picnic. Wives and children come out on ponies and we drive the ground, it’s more like a grouse count. The butts have long since disappeared, so I place the Guns. In the 1960s the syndicate had eight days with an average bag of 15 brace on each, this year they limited the whole season’s bag to three grouse. The aim is eventually to fund David’s work through one or two let days per year. There is still a way to go, but the syndicate is fully supportive of the broader conservation project and happy to keep going until grouse numbers return.

From the WG’s point of view one of the positives of the SMS approach is the potential through keepering to provide employment in remote upland areas. Another is the opportunity to engage the community and get more members of the public out onto the hill and enjoying the wildlife. David is confident this can be achieved provided existing laws, which require people to stick to footpaths and keep dogs on leads around livestock, are enforced. He said: Everyone involved knows we need to share this special place with everybody. They manage to do it on the grouse moors in the north of England so we can here.

Looking ahead, David is hoping to have an assistant keeper from October until the spring. Current funding is due to end in 2020 and he is hoping that should grouse numbers not yet be sufficient to pay for the management, the wider conservation successes such as greater numbers of curlew and other waders will persuade the Welsh Rural Development Programme to continue supporting the project. He said: I want to see viable Grouse shooting back in Wales with all the benefits to the other ground nesting birds that brings. As the WG has backed the project with considerable investment, I want it to repay their trust and to show that shooting can fund great conservation work.

GWCT Research in Practice

Sustainable Management Scheme

Sue Evans, GWCT Wales director

Following a pilot study in 2013, GWCT, CLA Cymru and FWAG Cymru gathered a number of grouse moor managers together to see if there was an appetite among them to reinstate active moorland management. After a successful joint bid for funding from the Welsh Rural Development Programme under the Sustainable Management Scheme (SMS) the group established the 16,000-acre North Wales Moorland partnership and the 20,000-acre Powys Moorland Partnership in Mid Wales with Cath Hughes acting as facilitator and continued guidance from GWCT.

The demise of wildlife in Wales highlighted by the 2013 State of Nature Report meant that a different approach was crucial in order to save the birds on the endangered list. The SMS focuses on tangible results or outcomes, gives greater flexibility to the farmers/landowners about how these can be achieved and works on a landscape scale through cooperative partnerships. This collaborative approach engages a much greater number of people from across the rural community and beyond, linking the preservation of natural resources to the nation’s health in line with the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015.

This article was written by Joe Dimblebey for the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Billy Bridgewater – Farmer and grazier (pt.1)

Billy Bridgewater is a farmer and grazier. He owns three farms, now run by his sons. For a time he bred ponies on the hills, for pit ponies. He is passionate about the grouse. First part of an interview with Catherine Hughes.

Farmer – Billy Bridgewater

Interviewer – Catherine Hughes

Music Soundtrack & Introduction – Jeremy Creighton Herbert

Sound Recordist – Jeremy Creighton Herbert

Billy Bridgewater – Farmer and grazier (pt.2)

Billy Bridgewater is a farmer and grazier. He owns three farms, now run by his sons. For a time he bred ponies on the hills, for pit ponies. He is passionate about the grouse. Second part of an interview with Catherine Hughes.

Farmer – Billy Bridgewater

Interviewer – Catherine Hughes

Music Soundtrack & Introduction – Jeremy Creighton Herbert

Sound Recordist – Jeremy Creighton Herbert

Keep in touch, get involved.

We will be putting on various events over the next 12 months. If you would like to get involved, have some ideas please contact Catherine on urmyc.sdnalroomsywop@tcatnoc